I have to confess this is something of a digression, as I ponder why one of our plantings from early summer has fared so poorly. But, as it’s been a while since my last post, I will cut myself a bit of slack….

I have to confess this is something of a digression, as I ponder why one of our plantings from early summer has fared so poorly. But, as it’s been a while since my last post, I will cut myself a bit of slack….

Many gardeners are, quite rightly, a little obsessive about the soil in their gardens: its apparent shortcomings and remediation are as perennial a subject of conversation amongst gardeners as the weather is for everyone else. So spare a thought for those who, perhaps because they are building a new home, are faced with importing soil onto the site to create their garden from scratch. The chances are they won’t really know what their soil comprises before it arrives, and maybe not for a while thereafter. Unless they are very lucky, in all probability it will be a manufactured, sterile product of indeterminate origin. Hopefully subsoil and topsoil will at least conform to generally accepted criteria and have been delivered and spread in the right order(!). Anything more is a bonus.

Topsoil

There is a British Standard for topsoil – BS 3882:2007 “Specification for Topsoil and Requirements for Use” – which attempts to classify multipurpose and special purpose topsoils being moved or sold. It addresses lots of attributes like pH, nitrogen, phosphorus, magnesium and potassium content, organic matter, soil texture and contaminants. Anyone buying topsoil would be well advised to buy a compliant product. However, what it doesn’t address are living organisms!

All plants need topsoil if they are to survive. I’ll say that again. All plants need topsoil. Subsoil won’t do. Why? Because plant roots can only do their job with the help of a complex ecosystem of insects, fungi, and microorganisms that enable the plant to obtain the nutrients it needs from the soil. And the presence of that ecosystem, together with other organic matter, is what fundamentally differentiates topsoil from subsoil. Of course, plants roots need air and moisture too, and this living ecosystem plays a vital role here as well.

Soil Organic Matter and Humous

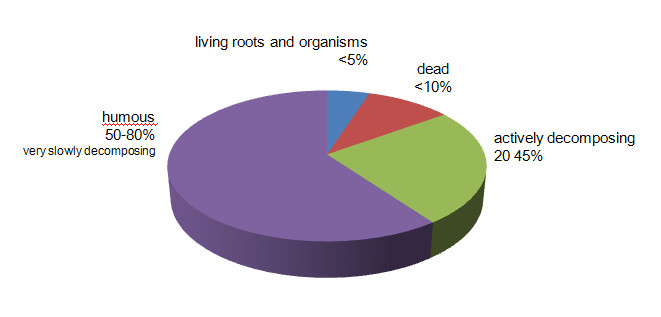

Soil organic matter is made up of a wide variety of materials derived from plants, animals, and soil organisms, which can be divided into four categories:

- living organisms and roots, making up less than 5% of the total;

- residues from dead plants, animals and soil organisms that have not yet begun to decompose (<10%);

- material undergoing rapid decomposition (20-45%);

- stabilized organic matter (humus) remaining after further decomposition by soil microorganisms (50-80%).

Humous (the stabilized organic matter) has the longest lasting benefits for gardeners. It is a mix of stable, complex organic compounds formed during initial rapid decomposition, which decomposes only slowly over time (about 3% per year). Humus comprises a mix of solid particles and soluble compounds – sugars, proteins, gums, fats, waxes, resins and lignin – that are too chemically complex to be used by most organisms but improve the physical and chemical properties of soil by:

- binding mineral particles together into larger aggregates, which helps to improve air and water infiltration and movement;

- improving water retention and release to plants;

- slowly releasing nutrients (e.g. nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur) over time;

- helping to retain nutrients that would otherwise be leached from the soil;

- providing a “buffer” that stabilises soil pH; and

- chelating (binding) toxic metals in soil.

Soil supplied to BS 3882:2007 should at least have a modest organic matter content: the specification for general purpose topsoil is 3-20% (a rather wide range). However, it doesn’t distinguish between the different categories of organic matter, and could still be completely devoid of that all-important humous: in such a case it could take several years before a satisfactory humous content is established.

Soil Organisms

Of the circa 5% of topsoil that is typically organic matter (it can be up to 30%), about 0.2% comprises living organisms, albeit mostly invisible to the naked eye. One cup of undisturbed soil typically contains:

- 200 billion bacteria

- 20 million protozoa

- 100,000 meters of fungi

- 100,000 nematodes

- 50,ooo arthropods

Some of these have a close symbiotic relationship with plants, including rhizobia and mycorrhizae.

Rhizobia are bacteria that establish associations with plants such as beans and peas (legumes). They form nodules on the roots where they “fix” nitrogen gas from the air and in return the plant supplies the bacteria with essential minerals and sugars.

Mycorrhizae are specific fungi found in most soils that have symbiotic associations with plant roots. They are very host-specific (i.e., each plant species is associated with specific species of mycorrhiza) and enlarge the surface-absorbing area of the roots by 100 to 1,000 times by creating filaments or threads that act like an extension of the root system. In exchange for making the roots of the plant much more effective in the uptake of water and nutrients, the fungus gets essential nutrients from the roots to fuel its own growth. Mycorrhizae enhance the plant’s ability to tolerate environmental stress and reduce transplant shock.

Glomalin, which improves soil tilth, is a glycoprotein produced as a by-product of mycorrhizal activity. Glomalin, together with humic acid, is a vital constituent of soil organic matter that improve soil structure by binding the tiny clay particles together into larger aggregates, which in turn increases the pore space and helps to create an ideal environment for roots.

There are many other indirectly beneficial soil organisms, including microorganisms, insects and worms, which act to decompose soil organic matter into forms that can be used by plants, and also improve the soil structure. Most of the soil-obsessed gardeners I mentioned earlier will know organic matter improves soil structure: perhaps not everyone knows the beneficial properties are only realised with the help of soil organisms.

Earthworms are perhaps the best known soil organism – described by Aristotle as “the intestines of the earth”. In fact there are many different species of earthworm, which fall into four different categories:

- Anecic earthworms build permanent burrows deep into the soil. They feed on leaves on the soil surface that they drag into their burrows. Our dear friend Lumbricus terrestris is probably the best known species: it lives in a vertical burrow up to 3m deep, which it occupies for its entire life cycle. L. terrestris reaches sexual maturity in about 52 weeks and they can live for up to 10 years. They are typically dark coloured at the head end (red or brown), with paler tails.

- Endogeic earthworms live in, and feed on the soil. They occupy horizontal, non-permanent burrows in the upper mineral layer of soil, and are not usually noticed except after a heavy rain when they come to the surface. Some can burrow very deeply in the soil. Endogeic earthworms are often pale colours – grey, pale pink, green or blue.

- Epigeic earthworms live on the soil surface in leaf litter. They tend not to make burrows but live in and feed on the leaf litter. Epigeic earthworms are also often bright red or red-brown (but they are not stripy).

- Compost earthworms are, unsurprisingly, most likely to be found in a compost pile. They thrive in warm, moist environments with a ready supply of fresh compost material (which they very rapidly consume). They also reproduce very quickly. Compost earthworms are mostly bright red and stripy.

In all, there are some 26 species of earthworm in the UK. Charles Darwin wrote a paper on earthworms during his later years, in which he speculated that almost all of the fertile soil on earth must have passed through the gut of an earthworm. Perhaps he exaggerated, but ….

Earthworms are just a few of the many organisms that decompose organic matter in the soil and improve the soil structure. The deep burrows of anecic earthworms create passages for air, water and roots, facilitating the exchange of soil gases with the atmosphere – clay soils particularly benefit from extensive earthworm burrows. Anecic worms enhance soil organic matter and humus by dragging litter into their burrows. Endogeic burrows contribute to soil tilth, increasing soil porosity. (If you’re interested in learning more, you can even join the Earthworm Society of Britain ![]() .)

.)

Soil organisms can be encouraged by:

- Adding organic matter: organisms require a food source.

- Applying an organic mulch: helps to stabilise the soil temperature and moisture, and helps prevent compaction.

- Avoiding the use of pesticides, some of which are devastating to soil organisms.

- Minimising cultivation, which can kill earthworms, destroy worm burrows and mycorrhizae, and damage the soil structure.

- Maintaining moist soil conditions (but avoid over watering).

As I mentioned earlier, the BS 3882:2007 standard doesn’t address soil organisms at all. In fact quite a lot of commercially available topsoil is completely sterile – devoid of any organisms, and with the organic matter provided simply by adding fresh mulch-type material from recycled “green waste”. Obviously, it could take several years before such a “manufactured” topsoil exhibits the level of fertility we would expect.

So, if you need to import topsoil, it really is worth trying to find a local source of natural topsoil, for example from a local construction project.

And what about that struggling planting I was supposed to be investigating? Well, the manufactured subsoil and topsoil complied with BS 3882:2007 and were certified by a soil consultant to be suitable for landscape planting. But with a soil texture that sets like concrete when dry, a pH of 8.3 and an organic content comprising a smattering of woody lumps, I’m wondering if it isn’t just a mix of clay, crushed concrete and wood chips! It could be a while before our plants thrive ![]() .

.

A Footnote on Soil Inoculation:

Generally, the results of inoculation with mycorrhizae can be inconsistent, because they are species specific. They also have a limited shelf life so, if you do want to try it, buy a fresh product. Commercial farmers growing legumes may use rhizobium inoculation, but the best tip for the gardener is simply to grow your runner beans on the same patch each year (against our crop rotation instincts, I know, but it generally works). Inoculation with other organisms is generally not necessary.

Svend